Monocle, June 2019

Despite challenges both past and present, canny redevelopments, scrappy fundraising and passionate residents have ensured this city’s regeneration has rock-solid foundations.

Little Rock likes to tell its visitors that everything sounds better with a southern accent. A city of drawlers, the Arkansas capital helped forge the career of Bill Clinton: it’s where he served as governor and launched his presidential bid, turning the city’s favourite dive restaurant, Doe’s, into his de facto campaign headquarters. Yet for a long time, Little Rock was making noise for all the wrong reasons.

A metropolis of just over 200,000 residents, Little Rock found notoriety during the civil-rights movement when, in 1957, nine black students attempted to desegregate Central High School against the wishes of the state governor. The national guard and an airborne division were sent in. A few years later, the city was still licking its wounds from the Little Rock Nine debacle when swathes of downtown were demolished under a so-called federal urban-renewal scheme, which entrenched social divisions even further. The free market was meant to step in but instead, white flight left the urban core (and those who still resided there) neglected. To add to Little Rock’s woes, the 1990s rolled around with headlines of spiking crime rates and gang violence. The city needed saviours; enter its city fixers.

Stroll around downtown’s River Market or Southside Main Street areas today and it would be hard to deduce the city’s chequered past. Empty lots are no more; bars and restaurants are busy. The city boasts a venerable cultural institution in the Robinson Arts Center, since it underwent a $70.5m (€62.5m) renovation in 2014 and reopened in 2016 as part of a creative-corridor plan. A year later a Technology Park was also established in

the city centre – a homegrown bid for a part of the national tech boom. Many of these ideas were promoted by the city’s former mayor, Mark Stodola. He spent 12 years in office until the start of this year, as well as a term as president of the National League of Cities, an ngo that has more than 2,000 member US cities. “Until I became mayor, Main Street was dead,” he says sitting in the bar at the historic Capital Hotel.

Stodola also recognised the value in working closely with people such as Jimmy Moses, a developer who says he caught the “city bug” as a kid. Moses is one of the founders of Newmark Moses Tucker Partners. After studying in Virginia and Florida, he was toying with relocating to Boston or San Francisco until the best-paid job offer landed him back in Little Rock. “That was fortuitous for me,” says Moses with a grin, “because it took me several more years to work out that my real life’s work was to be a real-estate developer and use my love of Little Rock, and my training, to try and rebuild a city.” Today Moses’s work includes 19 downtown refurbishments and 10 new-build residential towers.

Moses’s latest venture is in the East Village, a formerly industrial and neglected part of town that has started to develop. Partnering with Cromwell Architects, a former bike-repair shop has been turned into a barbecue restaurant, while an old paint factory has been transformed into Cromwell’s HQ. The upper level comprises loft rentals designed to “test the market”, according to Moses, by luring young professionals to the newest part of the urban core (all but one is leased).

As Cromwell’s Dan Fowler puts it, pointing to the exposed board-form concrete of his open-plan office, the redevelopment of historic building stock is a chance to be a Little Rock pioneer. “We wanted to be a leader in how you save a building like this and repurpose it, making it a rich part of the history and tradition of the city.”

The uptick in the fortunes of the eastern corridor wouldn’t have happened without the nearby anchor tenants. Bill Clinton’s presidential library and museum opened in 2004 on a grassy campus. Since then, non-profit Heifer International has been built beside it, while the Clinton School of Public Service – a master’s programme with up to 45 students a year – has operated out of a fin de siècle former railroad building since 2005. According to estimates, the library alone has brought in $2.5bn (€2.2bn) of public and private investment for the city since it was announced in 1997.

For Dean Kumpuris, one of the people charged with convincing Clinton to locate the library in Little Rock, the site that won the hard-fought bidding process represented inclusive redevelopment, which is why the Clintons “bought into the vision”. Gastroenterologist Kumpuris (every inch the southern gentleman in his bow tie and jacket) first tried to better his city in the 1990s when a mini-revolt over planning led to a new era of civic engagement and a less top-heavy way of governing. During that period “the good doctor”, as he has jokingly been referred to, went from concerned citizen to member of the city board – a position he hasn’t relinquished. Kumpuris meets monocle at a sculpture garden on the edge of the Arkansas River, near River Market – another Moses project. “Every weekend I come here and spray the weeds and imagine how things could be,” he says. “I’ve been doing it forever; I’m a little crazy.” Beyond is the newly opened Margaret Clark Adventure Park, a playground for pre-schoolers that includes animal sculptures perfect for climbing.

Both Moses and Kumpuris echo the notion of team effort. Moses talks of the friends, family and colleagues who have cobbled together the funds for the firm’s projects and become stakeholders, citing “love for the city and passion about what we do” over financial gain. Kumpuris, who was instrumental in corralling funds for the sculpture park and playground, admits that it can be an “absolute scrap” raising money. Almost all of Little Rock’s leaders enviously eye the northwestern corner of Arkansas, where the vast coffers of Walmart’s Walton family in particular have funded institutions such as the Walton Arts Center and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. But Kumpuris says that would be “too easy” for Little Rock.

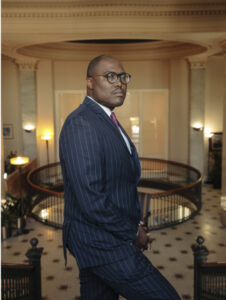

Another concern is that many of Little Rock’s civic fixers are starting to age; Kumpuris points to the need for a “new cadre” of leaders. Meaning all eyes are on the newly installed 35-year-old mayor Frank Scott Jr. The city’s first elected black mayor recognises the “historical relevancies” but rebuffs the symbolism, saying he simply ran to be mayor of his hometown. Like many of Little Rock’s emergent leaders, he says that while one has to understand the racial issues of the past, he doesn’t think it needs to be a constant part of the discourse.

Scott nevertheless ran on a ticket of unifying Little Rock, a metropolis that had its divisions cemented by the 630 and 30 interstate highways that cut off the less privileged east and south areas from the rest of the city. “We have many neighbourhoods and communities that are within a three-and-a-half-mile radius that do not talk to one another.”

Scott’s challenges include improving infrastructure, lowering violent crime rates and dealing with the accusations of police overreach through the use of so-called “no-knock” warrants (entering properties without prior notification). Yet the mayor says the media has always had a myopic view of Little Rock. “We have to embark upon a branding exercise, sharing our story,” he says, adding that Little Rock – which is diverse, and both urban and rural – is “a microcosm of the United States”. Sitting beside Scott in the downtown restaurant where they first met is his former boss from First Security Bank, John Rutledge, now a member of his transition team. Citing the river port, the nearby airport and the interconnectivity of the interstates, Rutledge adds: “We’re sitting in what could be a logistics hub for the middle part of the country.”

Rutledge argues that his family’s community bank is “only as good as the communities you’re in”, so he has a vested interest in seeing Little Rock prosper. That’s why First Security has helped fund a range of initiatives, including the Tech Park and an amphitheatre by the river. But if the city is going to flourish further it will also have to win back people who have flown the coop. Today, two of Little Rock’s main cultural players are returnees. Eliza Borné, the editor of Oxford American magazine, spent three-and-a-half years in Nashville before working her way up the rungs at the music and literature publication. Kathryn Tucker, a founder of Little Rock-based Arkansas Cinema Society, whose father works with Moses, came back after a stint in Los Angeles.

Both Borné and Tucker say family played a big part in their decisions to return. But Little Rock also offers the chance to be part of a small, tightknit creative community – and make tangible differences at the same time. Borné says that both she and her circle of friends are committed to making Little Rock “as culturally vibrant as possible”. Oxford American, by way of an example, programmes concerts with South on Main restaurant. Tucker, meanwhile, volunteers at an elementary school in the hope of nurturing a new breed of Arkansian scriptwriters and directors, alongside the Cinema Society’s work programming talks with directors.

“The cool thing about living here is the impact that one person can have on a community,” says Tucker. While it can be difficult at times, doing it where you were born and raised makes it all the more satisfying. “You know what home feels like,” she adds. “It’s just home.”

Thinking globally:

The Global Solutions Institute was conceived in 2012 to make Little Rock a global leader in technology, covering energy, water, clean air and food that can help the developing world. Overseen by Mark Grobmyer, it is raising capital to build a large campus that will include an expo hall. The aim? Provide a space for permanent demonstrations from companies in the sector, to show how the technologies will work in practice. Grobmyer says that while tech parks exist, nothing tackling deployment has been attempted before. “I wanted to do something [in Little Rock] that would create enough opportunity for any of my children or grandchildren to be able to do something here that’s just as important as if they were in New York or London or Tokyo,” he says.