Little White Lies, January / February 2009

As the legacy of Che Guevara continues to be felt in Latin American politics, how is his spirit interpreted tody. And who is the most likely candidate to assume his mantle?

His flyaway hair spills out of a trademark beret as he stares into the middle distance; in his eyes there’s a look of steely determination and an air of committed revolt. As Alberto Korda captured Che Guevara in 1960, the Cuban photographer could have had little idea that his photo would become the iconic image of contemporary revolution, resonating with dispossessed and disenfranchised groups all over the world.

Getting past the mythology can be a tricky business; such is the power of brand Che. He was a man of unwavering commitment who fought for what he believed in until the end: Ernesto the middle-class Argentine doctor became Che, the man of the people who refused to condone social inequality. A fiercely doctrinal Marxist, he wrote profusely, from his Bolivian Diaries to the much lauded revolutionary manual, Guerrilla Warfare. Where opinion wavers is the extent of his brutality in achieving his goals. The popular image of Che skirts over this point, and his biographers Jorge Castañeda and Jon Lee Anderson vary in their opinions. For British writerRichard Gott, there’s an “iconic myth of Guevara as a soft and cuddly individual,” when in truth he was “as tough as nails”. Anderson, meanwhile, tells LWLies that Che was “a real revolutionary” – a killer who believed in armed struggle, but who was “not brutal in the sense that he enjoyed killing or went out of his way to kill civilians”.

Yet in today’s political climate, it’s the remarkably unifying power of his name and image that has become more important than the finer details of his character. For Che has become a revolutionary chameleon: a symbol of pan-Latin American unity; of egalitarianism; of edgy anti-establishment angst; of just about any vaguely militant left-wing cause. Contemporary revolutionaries, and the pretenders to his crown, understand the potency of both who Che was and what he was seen to be. Harnessing the myth is key.

The world has changed radically since Che was at the height of his guerrilla activity. The Soviet Union has collapsed, Eastern Europe has turned towards the European Union, and China, although socialist in name, has embraced a market economy. Even Cuba, the isolationist and embargoed vanguard of communism, has loosened its fiscal chastity belt since Fidel handed over the keys of power to Raúl in February. Pragmatism on the part of the authorities, or an admission that there needs to be a third way: Che would surely be turning in his grave at this capitulation of global communism. But these changing and very different circumstances demand a new sort of revolutionary, one that can take Che’s teachings, learn from his mistakes and reformulate them for a post-modernist world. There’s even an argument that the age of revolutionaries has passed, although this is flatly refuted by Cuba expert Charlie Nurse from Cambridge University’s Centre of Latin American Studies. “There are plenty of societies with a combination of deep-seated grievances and repressive governments,” he says. “This seems to me to suggest that revolutionary movements – and leaders – will continue to exist.”

While Che has always been traditionally championed by those on the fringes of the Latin American political landscape, in recent years he’s moved into the mainstream. This is thanks to what the media likes to term the ‘pink tide’ sweeping South America. A reaction to years of right-wing military dictatorships, from Brazil’s Figueiredo to Chile’s Pinochet, South Americans have voted in a string of leftist heads of state in recent years that includes Fernando Lugo of Paraguay and Rafael Correa of Ecuador. The most high profile – and most militant – of these presidents are Hugo Chávez of Venezuela and Bolivia’s Evo Morales.

In his weekly televised speeches, Chávez constantly invokes Che Guevara alongside local hero Simón Bolivar. Chávez is an unashamedly populist leader who realises the power of Che in justifying his self-declared revolution. He was among the first Latin leaders to lay a wreath at Che’s Cuban grave last year when the world marked 40 years since his death. Chávez is vigorously anti-imperialist and anti-American, sentiments shared by Che, who openly criticised Russia’s courting of US political opinion in the 1960s. But there are, of course, skeletons in the Chávez closet – tales of corruption and authoritarianism. Meanwhile Chávez defends himself by accusing the ‘Yanquis’ of fabricating lies about him.

It is still too early to assess how much Morales really embodies the spirit of Che. Like his Venezuelan counterpart, he claims huge inspiration from the Argentine. He was once asked in an interview whether he was the new Che, and replied: “The people will have to decide… Che is my symbol.” Like Chávez, Morales draws on Che’s pan-Latin Americanism. Elected in 2006, time will tell whether Latin America’s first indigenous president can transform one of the continent’s poorest countries and realise Che’s dream of a radicalised and revolutionary rural population. Jon Lee Anderson sees potential, but questions whether he can go “all the way in the pursuit of the Guevarist ideal”.

The gap between politicians’ rhetoric and their actions is often large, however, and, for all their talk, Latin American leaders don’t always follow up on their moral assertions. The really radical work has often been left to traditional guerrilla movements – armies and militias that believe only armed struggle against government inertia will see their demands met. The list of Marxist-Leninist groups to have emerged from the region’s jungles since the ’60s is long and complicated. The most famous of these include El Salvador’s FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front), Nicaragua’s Sandinista National Liberation Front and Guatemala’s Guerrilla Army of the Poor. All claim Che as an inspiration in their fight for justice and equality. Fast-forward to 2008, however, and many of the groups have withered, disbanded or mellowed their message and joined the political centre: in the case of the Sandinistas, leaderDaniel Ortega has become president – twice.

One of Latin America’s oldest and most famous revolutionary movements is FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). Founded by Manuel Marulanda (born Pedro Antonio Marín Marín; he renamed himself in honour of a murdered trade union organiser), he represents the more confrontational side of Che’s character, having been at war with the Colombian state for more than half a century. FARC are an anomaly though, arguably pushed into formation by the communist witch-hunt that followed the civil war of the ’40s and ’50s known as ‘La Violencia’. Marulanda has constantly been forced onto the back foot by the government, assuming his communist persona as a means of survival, where Che was much more an ideological Marxist. Marulanda’s tactics wouldn’t have washed with Che either: FARC siphon drugs money by taxing coca farmers, and have a penchant for high profile extortion and kidnapping. Ironically, FARC were recently duped into releasing Franco-Colombian politician Ingrid Betancourt by Colombian officers posing as fellow rebels by wearing Che Guevara T-shirts. With this episode, FARC’s aura of invincibility was finally shattered and, with Marulanda’s death in March at the age of 77, the future looks uncertain.

The demise of FARC is arguably symptomatic of Latin American guerrilla movements as a whole. Yet one leader remains, somewhere deep inside the south Mexican jungle, who continues to carry the torch for revolutionary – and anti-globalisation – movements worldwide. Subcommander Marcos burst onto the world scene in 1994 when his group of peasant fighters captured several small towns in the state of Chiapas and demanded equal rights for Mexico’s indigenous people. He quickly became an international media sensation with journalists saluting him as the new Che Guevara. Similarities between the two leaders are numerous: both middle-class, white and educated; both poetry-lovers and prolific writers; both prepared to reject privileged backgrounds to improve the lot of the downtrodden.

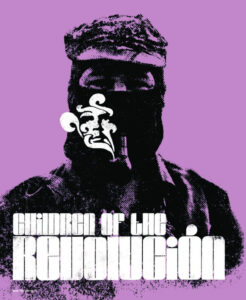

Che has had an obvious effect on ‘El Subcomandante’ and Marcos clearly understands the awesome potential of his image. To say that he’s tapped into Che’s myth would do him a disservice, but he’s seen how Che has been lionised since his death and has learned from it. For Marcos, the self-invented mystique helps sustain media attention in his cause and, although his real identity (Rafael Guillén) has long been known, he always appears in black balaclava, army cap and fatigues, often on horseback and with a pipe clenched between his teeth. It’s an instantly iconic warrior-like image of a man fighting for the rights of Mexico’s little people. The media, of course, laps it up and whenever the spotlight has threatened to shift away from Chiapas, Marcos – ever astute – has issued a communiqué or organised a march to regain interest.

Yet Marcos doesn’t play a ruthless endgame. Since the 1994 uprising, he’s realised that violence isn’t the answer. While Che looked at his revolution through a haze of gunfire and grenade smoke, it’s Marcos the orator – not the fighter – that has triumphed. Marcos became a guerrilla out of Marxist conviction, but conditions in Mexico never seemed ripe for the sort of radical overthrow of the ruling elite that Che advocated. Marcos was able to read this mood and adapt his way of thinking – Che ploughed on regardless. “Marcos has clearly stated that it’s not so much Che’s achievements or his methods that he admires,” Marcos biographer Nick Henck informs LWLies, “rather his idealism, self-sacrifice and leading by example, all of which imbued Guevara with considerable moral authority.”

If there’s an evolutionary chain of revolutionaries, then Marcos is surely the next in line after Che: a more adaptable, less entrenched vision of modern-day struggle. As for the future of revolution and armed resistance in Latin America, perhaps Marcos represents the beginning of a new chapter in which words not weapons triumph. Of course, this utopian scenario relies on the new breed of left-wing South and Central American politicians redressing the huge social inequalities that continue to exist in the region. If not, then a new leader will no doubt emerge to follow in Che Guevara’s real and mythical footsteps.