Monocle, September 2019

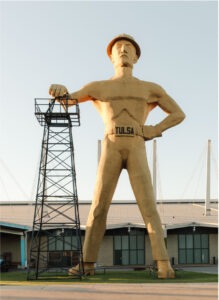

The latest stop in our series is Tulsa. Despite a slowing trickle of oil money it is rich in creative vision and optimism for the future; now it just needs to get the rest of the world on board.

Dressed in a seersucker suit, architect Ted Reeds stands in the centre of the cavernous lobby of a high-rise and gazes towards the Gothic-style travertine ceiling. Built in 1928 by philanthropist and oil magnate Waite Phillips, the Philtower Building is one of the standout examples of the era’s meticulously crafted and often opulent buildings that remain in downtown Tulsa, Oklahoma’s second city. “Phillips sowed the seeds of modern Tulsa,” says Reeds. “He brought the idea of giving back more to your community than you take out.”

Reeds, who occasionally acts as an unofficial architecture tour guide, highlights Tulsa’s boom-time place-making and proclivity for benevolent largesse, which were lubricated by one industry: petroleum. The city was the oil capital of the world until the industry migrated south to Houston in the 1980s. Despite a relative loss of influence, the money has remained: the Tulsa Community Foundation, a collective of donors who give to everything from animal-rescue centres to education initiatives, is the second largest such foundation in the US outside of that provided by Silicon Valley.

While Tulsa may have the sort of private capital that would make most cities go weak at the knees, that doesn’t mean there aren’t problems to solve, including how to sell itself to the outside world. Several questionable branding attempts haven’t helped: “Comfortably cosmopolitan” for Tulsa and “Oklahoma is OK”, a play on how the state name is abbreviated that sounds like a celebration of the mediocre. That’s why George Kaiser is on a mission to put his city firmly on the map.

Spend any time in Tulsa and it isn’t long before the Kaiser name comes up. An outspoken Democrat in a staunchly red state, the 76-year-old has a net worth of $7.4bn (€6.6bn) thanks to a career in banking and oil. Although he’d rather talk up the early-years education that his George Kaiser Family Foundation funds (he also set up the Community Foundation). He’s heavily involved in civic life too.

Kaiser meets us, appropriately enough, at what is arguably his crowning community achievement to date: Gathering Place on the banks of the Arkansas River. A lush $465m (€417m) park that opened last September, it will span 40 hectares once the second and third phases are complete. “We’ve focused on creating distinguishing characteristics,” he says. “And this park can create an image of something that is unique and unexpected.”

Put another way, Kaiser wants to make you look again. He thinks “a minimum level of vibrancy in the economy” will help make Tulsa an alluring destination for young talent. Which is why his foundation is behind the decision to pay people a $10,000 (€8,970) bonus to work here for a year in the hope that they’ll stay. It’s part of the “Tulsa Remote” programme that has 50 people enrolled, with the number set to rise to 80 by the end of the summer.

It doesn’t stop there. The George Kaiser Family Foundation has also been involved in the regeneration of the Arts District – just over the rail tracks from downtown – where it owns several buildings and has funded jazz bar Duet. It has also bought folk singer Woody Guthrie’s archive and turned it into a museum. In addition, Kaiser and the University of Tulsa paid up to $20m (€17.9m) for Bob Dylan’s archive, which will open to the public in 2021. For Kaiser, art, music and nightlife are all reasons for people to stick around – and could help increase the population, which has hovered at about 400,000 for more than two decades.

He’s not the only one at it. Across town, Mother Road Market is a new food hub opened by the Lobeck Taylor Family Foundation in a former warehouse dating from 1939. There are more than 20 restaurants and retail spots; on a weekday afternoon the place is teeming. “Part of what makes a city cool is what food options there are,” says Elizabeth Frame Ellison, the foundation’s CEO. The market serves multiple purposes: it entices people from the suburbs to try something different and improves Tulsa’s culinary offerings.

The market also has an incubator called Kitchen 66. Start-ups can rent commercial kitchens and even sign up for a four-month mentorship, which takes entrepreneurs from idea to market for their product. Both Frame Ellison and her mother Kathy Taylor – a former mayor and co-founder of the foundation, alongside husband Bill Lobeck – are adamant that it isn’t charity. For one, people pay for the course (even if it can be on a what-you-can-afford basis) and after a year of subsidised rent in the market, Kitchen 66 participants are offered another year at full rate. Then, according to Frame Ellison “the apron strings are cut”. Taylor adds, “Every programme we strive to run so that it pays for itself and becomes profitable.”

Both Kaiser and Taylor admit that foundation money isn’t always the best – nor the most democratic – model for a city. While people largely think that the work the foundations do is constructive, there are some concerns that they create a culture of either being in the benefactor club or not. Mayor GT Bynum doesn’t see it that way. “I will tell you that every mayor in the US would trade their left hand to get the philanthropic community that I have here,” he says from city hall.

Both Mother Road Market and Gathering Place aim to bring together Tulsans from all races and backgrounds, something that gets to the heart of one of the city’s main challenges. In 2021 Tulsa will mark the centennial of the US’s worst race massacre. It took place in its Greenwood area – once home to a thriving financial centre known as Black Wall Street – when a mob of white residents attacked and killed some 300 African-Americans. In a city that still suffers from de facto segregation and at times clumsy conversations over race, Ricco Wright wants to mature the debate. A former professor and a University of Columbia PHD graduate, he returned to Oklahoma from New York to “give back”. He’s since opened an art space, Black Wall Street Gallery, and started a series called Conciliation, pairing one white and one black artist. His gallery has become an anchor tenant on the street and he’s determined to fill the empty lots that remain with black-owned businesses. “I want us to become a progressive city,” he tells us, on an evening when the gallery is throwing a block party. “I want us to address our issues.”

Antoine Harris does too. One of Tulsa’s few African-American developers, he formed Alfresco Group in 2016 with a determination to upend the assumption that North Tulsa – the majority black part of town – is a bad investment. We head to a rolling patch of grass with distant views of downtown. It’s the site for a future boutique hotel that will also feature commercial space, part of a masterplan for the northern corridor. “The system says North Tulsa is not profitable,” he says. “I’m out to prove that wrong.”

Tulsans clearly want their home to be seen as a big city – and there are plenty of people pushing to make it happen at a micro level. But perhaps Henry Aberson is the biggest testament to the opportunities that Tulsa offers. He is behind Center 1, a collection of shops, galleries and restaurants in the Brookside neighbourhood. He’s turned the district into a retail destination and says he would have struggled to do that in a more expensive city. As well as bringing in big national brands, he has nurtured local retail players, such as Black Optical. Why has he done it? “I had this stupid idea,” he says, “that nothing is too good for Tulsa.”

Lessons from Tulsa – how to make a second-tier city work:

1. Tulsa needs a recession-proof commerce sector as the city is reliant on sales tax for its operations (like all cities in Oklahoma). Places such as Mother Road Market realise F&B is a key sales-tax generator that can help city coffers.

2. The city celebrates its architectural past. The renovation of Tulsa Central Library and the overhaul work on Gilcrease Museum show that design is still at the fore.

3. A talented workforce needs reasons to stick around. George Kaiser has been instrumental in creating them, not least with Gathering Place park