Monocle, May 2012

As an aspiring superpower and regional leader, there’s a lot at stake for Brazil’s command of the UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti – especially as the drawdown begins. Monocle spends time embedded with troops in Port-au-Prince.

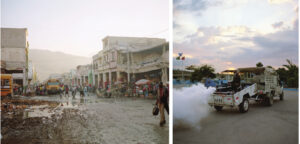

Rush hour in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, and the main road from the airport is clogged. The UN’s trademark white jeeps are crawling back to General Barcellar Base, home to the First Brazilian Battalion helping lead the mission to stabilise the country. The barracks are a bastion of order in a city still struggling to recover from the devastating earthquake two years earlier. Government figures claim an estimated 316,000 lost their lives that January afternoon.

As the sun makes its descent, troops file back past a sentry post. A group of about 50 soldiers in exercise gear, a model of choreography, turns a corner on the tarmacked road. Following closely behind them, a truck bellows white smoke: a fumigation team to keep malaria at bay.

The final act of the evening is provided by a lone trumpeter. This is the signal for the lowering of the three flags mounted near a memorial remembering the 18 Brazilians who died in the 2010 quake. In the middle is the UN insignia; to the right, the navy and red of the Haitian flag; to the left, the Brazilian national colours. “It’s important to have Haiti on the right. It’s the more important position,” says Lieutenant Colonel Márcio Tibério. “We’re here as guests.”

“Guest” is a word repeated often during monocle’s time embedded with Brazilian forces, carefully invoked at every stage. The mission continues to court controversy, reeling from a cholera epidemic that followed the earthquake, linked to Nepalese soldiers. Cases of sexual abuse against Haitians have dented its reputation further still.

There are 11,109 UN uniformed personnel from 20 different countries in Haiti.But Brazil occupies a unique position within Minustah, the acronym given to the mission. With some 2,200 soldiers – and responsibility for policing the most volatile neighbourhoods in Port-au-Prince – Brazil is the biggest contributor of troops, and operations leader. It also supplies the force commander, a post occupied by Major General Luiz Eduardo Ramos Pereira when Monocle visits.

The commander’s office is located in Delta Camp, one of the mission’s nerve centres. Pereirahas just returned from a lunch with the UN Security Council, in town to review Minustah’s mandate, up for renewal every October. Responsible for security since President Jean-BertrandAristide was toppled in 2004, the UN voted to reduce troop numbers at the end of last year, with further cuts made in April. The mission is clearly eyeing an exit tragedy.

Pereira exudes easy-going warmth, showing off a collection of trophies on his coffee table and a framed picture of him skydiving next to his desk. He is also refreshingly open – something that causes the American press officer sitting in on the interview to wince on occasion – but keen to point out that there’s a lot more to the mission than negative headlines. “Brazilian troops did a survey with residents, including whether the UN should leave, and it came back about 85 to 90 per cent positive,” he says. “The majority of people like us.” He admits he would be lying, though, if he said he could control all the people under his watch. “If something happens, all this [good work we’re doing] gets thrown in the gutter.”

The 55-year-old says the role of force commander is a difficult one, bringing together soldiers from countries as disparate as Jordan and Japan, and juggling what is a part-military, part-political role. “It’s not a regulation, it’s an informal agreement,” he says, referring to the convention of having a Brazilian in his position. “And I’m proud to say that it has the support of the US; they think it’s good to have a Brazilian general here.”

An informal agreement it may be, but there’s also a clear Brazilian strategy. Over the past decade, beginning with the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as president in 2002, Brazil has sought to increase its influence in Latin America and beyond. Playing a greater role in UN peacekeeping missions, particularly one on its own doorstep, has been a key part of that plan. Lula visited Haiti three times during his presidency and his successor, Dilma Rousseff, who took over in 2011, flew in to see Haiti’s new president, Michel Martelly, earlier this year.

The decision was taken [to send troops] due to solidarity with a needy country in our area of influence,” insists the outgoing Brazilian ambassador Igor Kipman, about to swap Port-au-Prince for the more ordered environs of Bern. His office up in the hills of Pétionville affords impressive views of the capital’s chicest quartier, away from the rubble of downtown.

Kipman accepts that the reasons for his country’s presence in Haiti are not altogether altruistic, though. The gilded prize is a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, something that would cement Brazil’s status as an emerging superpower. “Of course being here and doing a good job for Minustah, recognised worldwide, has a reflection on our aspirations for a permanent seat. So it was not the reason why we are here but it is a tool to support our aspirations.”

Brazil is in Haiti primarily to provide security. Despite lofty aims of protecting human rights and strengthening democratic institutions, on the ground this amounts to policing first and foremost. With the Haitian army disbanded since 1995 and the Haitian National Police (HNP) in need of a helping hand, the Brazilian presence in slum areas – traditionally a hotbed of political unrest and drug-related violence – is essential.

The First Brazilian Battalion (Brabat1) set up a small base in Cité Soleil, one of the city’s most notorious shantytowns, in the aftermath of the earthquake. It has the air of a place erected with speed, dominated by giant field tents. A group of soldiers is preparing to go on patrol in the slum, strapping on bulletproof jackets, adjusting helmets and checking the two-way radio connection.

For Private Mauricio Rodrigues Santos, a fresh-faced 26-year-old, Haiti represents his first mission abroad. “Every day at 15.00 we start our patrol,” he explains. “It’s not that easy – this is a new experience for me. Having said that, it’s rewarding being able to help a nation like this that really needs it.”

The heavily armed convoy of jeeps and trucks sets out. The first stage of the patrol will be in vehicles, finishing on foot. Cité Soleil has a reputation for violence, infamous for breeding political gangs loyal to Aristide. Yet despite the obvious signs of poverty – shacks squeezed together, thin alleys with washing lines strung across them and chickens wandering around – much of it looks in better condition than the tent cities dotted around town.

The area feels calm and residents greet soldiers with “Bonsoir” (Haitians start to say good evening after midday). Excited children run up to the troops shouting “‘Ey you, ‘ey you” in English, wanting to bump fists. “When I was here in 2006 we couldn’t do a foot patrol like we’re doing now,” says Major Reginaldo Santos, Cité Soleil’s base commander, back in Haiti for his second tour. “There’s a big difference since last time. We can now walk calmly and talk to people. There were lots of gangs before.”

One of those areas is La Différance, a sparkling block that has been cleared of rubbish and given a fresh lick of paint. The Clean Block Project, a Brazilian initiative, has sought out 40 local families to take charge of the area’s cleanliness in the hope that the idea will spread outwards into the rest of the shantytown. Some 30 streetlamps have also been installed to help improve security.

La Différance is a shining example to the rest of Cité Soleil. But it’s hard not to notice the piles of rubbish in other parts of the slum blocking a waterway, sure to be a cholera hazard with the returning rains. “There are lots of areas that need work,” says Santos. “Our responsibility is security. Cleaning is the job of the government; but we do what we can.” The UN’s presence in Cité Soleil is, of course, sensitive. “We still need the Brazilian army,” says community volunteer Denis Gousse, 33, as we visit a biodigester co-project between Brabat1 and the Viva Rio ngo. “The gangs aren’t scared of the hnp but they’re scared of the Brazilian troops.” While Gousse is paying a compliment, his comment also speaks volumes about the power inequality that still exists between local and foreign forces.

Local pastor Jean Enock Joseph, who has worked in Cité Soleil for the past decade, recognises that Brazilian troops have helped arrest gang members and calm the neighbourhood. But he finds it difficult to separate the different nations – for him the UN as a whole is “complicit” in the cholera outbreak. “I would love for the security of my country to be handled by Haitian nationals,” he adds. “Unfortunately it’s Minustah.”

Security is not the only responsibility the Brazilian forces have. A military engineers company (Braengcoy) supplies 250 mission soldiers and their job includes digging wells, building bridges and tarmacking roads (they’ve laid 4,500km since August last year).

At Croix-des-Bouquets a tripod is set-up in the middle of the road as surveyors look at extending the tarmacked surface. A group of inquisitive Haitians watches. “The focus of the mission is not just about security nowadays,” says Captain Marcos Marcelo de Oliveira, looking up from the equipment. “And that’s what we do; improvements for the local population. The relationship between the local people and the engineers is very good. We normally spend the day with them and know them by name. The infantry doesn’t need to interact so much. Our work lasts days – sometimes months.”

On the jeep ride back to the base, the engineers in the front seat discuss their impressions of Haiti. “When I first came here I didn’t get shocked because we have some very poor areas in Brazil,” says First Lieutenant Aline Amado. The driver next to her, First Lieutenant Silva Oliveira, concurs, adding that “the pacification that happened here is very similar to the one that took place in Rio”.The similarities, though, go beyond Brazilian peacekeepers’ favela know-how. Brazil’s frontline involvement with Haiti since 2004 has clearly had an effect on the way it is perceived. On the main arteries of the capital – one of the world’s worst cities for traffic jams – the colourful public transport buses known as tap-taps sport images of Brazilian footballers such as Ronaldinho and Ronaldo. Haitians, big fans of murals, frequently paint Brazilian flags on their walls.

Brazil has become a place to look up to. Since the 2010 earthquake, some 4,000 Haitians have travelled illegally across South America and into Brazil’s Amazon region. Having heard abouttwo new hydroelectric dams and the construction boom sparked by the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Rio Olympics, it seemed like a logical place to look for jobs. Although Brasília has since clamped down, it has decided to grant 100 unconditional visas a month from Port-au-Prince.

Brazil and Minustah’s military mission may well be winding down as the security situation improves. The HNP now has over 10,000 cadets, up from 6,676 in 2004. But problems remain. Police numbers probably need to double, while there has been a recent spike in urban crime according to a study by Brazil’s Instituto Igarapé (physical assaults in Port-au-Prince jumped from 15.2 per 100,000 in August 2011 to 167.6 by February). The recent resignation of prime minister Garry Conille also shows that political instability could further undermine Haiti’s future.

Even if troops do leave, it is unlikely Brazil’s presence – from humanitarian aid to construction giant OAS’s private sector involvement – will disappear. “We have solutions that are much more adequate for African or Caribbean countries than solutions developed in Norway for example,” says Ambassador Kipman. “There’s a similarity in terms of soil, climate, needs and challenges. We made a lot of mistakes in the beginning. We can make sure Haiti doesn’t make the same ones.”