The Financial Times, June 17 2014

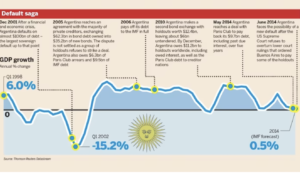

Cristina Fernández, the Argentine president, raised the prospect of a new sovereign default in a national address on Monday. She said her government would never succumb to “extortion”, after the US Supreme Court rejected an Argentine petition to reverse a legal ruling by a lower US court that forced Buenos Aires to pay holdout creditors.

Does the Supreme Court’s decision mark the end of the so-called “debt case of the century”?

Almost. It means that a 2012 ruling by New York District Judge Thomas Griesa remains intact. This verdict said that if Argentina continues payments to creditors who participated in two debt restructurings in 2005 and 2010, then it must also pay the full value of the bonds held by creditors who refused to take part in the deals. These are the so-called holdout creditors, led by NML Capital, a subsidiary of Elliott Capital Management, a hedge fund controlled by US billionaire Paul Singer.

Why doesn’t Argentina pay everyone and move on?

Of Argentina’s original $95bn default, about 93 per cent of creditors participated in the restructurings. Buenos Aires says that leaves roughly $15bn of bonds, including unpaid interest, in default. At stake in this case is a smaller sum: around$1.5bn worth of debt held by NML and its partners. Argentina can meet that payment, but, with only $28bn of foreign reserves, it cannot afford to pay the$15bn owed to all holdout creditors at the same time.

What options does Argentina have now?

Four, broadly. It could refuse to pay NML, but that would also trigger an automatic default on the exchange bondholders who participated in the restructurings. This would set back Argentine moves to regain access to international capital markets, such as its recent settlement with Paris Club creditors. That is a high price to payas Argentina needs fresh loans to develop its vast shale gas reserves. Indeed, on Monday Ms Fernández swore Argentina would continue to service restructured debt.

Second, it could continue to refuse to pay the holdouts, while maintaining payments to exchange bondholders. However, that would require rerouting payments outside New York, where the exchange bonds are settled. Logistically that is near-impossible, especially as the next payment, some $400m, is due on June 30. On this option, time appears to have run out.

Third, it could comply with Judge Griesa’s ruling, and pay NML and its partners$1.3bn immediately. However, that would open up Argentina to being sued by the exchange bondholders. That is because, until the end of this year, under a legal clause, they are entitled to claim any better terms voluntarily offered by Argentina to other bondholders.

That leaves a fourth option: reach an agreement with NML to settle its outstanding debts, probably by issuing fresh paper, but not until 2015 when the need for Argentina to offer similar terms to exchange bondholders expires. Even if politically difficult to swallow, this seems the most likely option at present.

What are the international implications of the case?

So far, none. There has been no market fallout and investors continue to snap up high yielding bonds issued by exotic sovereigns, such as Kenya and Ecuador. However, some, including the International Monetary Fund, worry that the case will make future debt workouts harder as it removes the incentives for creditors to participate.

Against that, others say Argentina has been so uniquely recalcitrant that its case does not set a general principle. Furthermore, most international bonds now have collective action clauses, which make a repeat impossible as it requires bondholders to accept majority decisions. Either way, the case has generated an unfortunate body of law – including a piercing of sovereign immunity. For example, the Supreme Court has also ruled that creditors can seek subpoena information about Argentine assets held around the world.

What a mess. Still, at least a victory for NML Capital?

On Monday Ms Fernández whipped out a chart which suggested that NML had made a 1,608 per cent return on the defaulted bonds that it bought in 2008. She said: “I don’t think that organised crime enjoys such rates of return in such a short time.” Yet it may not be so simple. Over the course of a decade, NML has racked up considerable legal fees. It probably hopes that other holdouts, freeriding on its case, do “the right thing” and help with its costs. That is ironic given that NML’s case relied on Argentina’s lack of collective action clauses.