Monocle, April 2018

Paraguay has been blighted by dictatorship, corruption and mismanagement. As the country goes to the polls will any candidate deliver real change? Many believe it’s now or never.

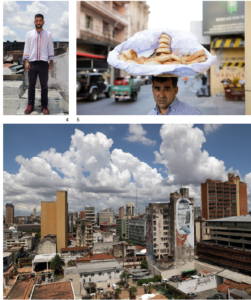

Summer in Paraguay’s sub-tropical Itapúa region, in the country’s south, can mean near-constant rain. It douses the cassava and yerba mate plants that grow in the area and spreads clay mud, the colour of oxidised blood, across the region’s asphalt thoroughfares. Sat on a step outside a petrol station here, Efraín Alegre – one of the country’s two presidential frontrunners – sips from a Styrofoam coffee cup, a mobile phone glued to his ear. Someone has managed to provide a plump cushion to protect the possibly-next-presidential posterior from the tiled surface. With weeks to go until the general election, this is what being on the Paraguayan campaign trail looks like.

Alegre, a career politician within the opposition Liberal party, won’t have it easy. He has to take on the mighty muscle of the Colorado party, which, apart from a brief lapse in the 2000s, has enjoyed more than 70 years of near-continuous hegemony, both autocratic and democratic. Which means Alegre and his team have to tear around the country campaigning at breakneck speed if they’re going to have a chance of tapping into growing frustrations with current Paraguay president Horacio Cartes. The incumbent is accused of attempting to manipulate both the justice system and the constitution among other ills. He’s made disparaging remarks about the LGBT community in the past and, more recently, thinly-veiled attacks against Alegre’s family.

For the Liberal presidential candidate, the Colorado dynasty needs to be stopped once and for all. “It’s the party that has caused the most internal instability in the country,” he says. Already today Alegre has dropped in on two agricultural cooperatives, attended a choreographed protest demanding better infrastructure and listened to testimonies from victims of the country’s 35-year military dictatorship – the longest in the continent, running from 1954 to 1989 – under the late Alfredo Stroessner, a member of the Colorado party. In many ways the country – ranked 135th out of 180 nations by Transparency International in last year’s Corruption Perceptions Index, second only to Venezuela in South America – is at a crossroads. Either it slips further towards failed-state status or it bucks the trend. The timing is ripe: Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and Brazil all head to the polls this year and corruption is front and centre in national debates.

Later that evening, Alegre puts a positive spin on proceedings. “We’ve managed to achieve an unprecedented alliance,” he says, a slightly overstated reference to Alianza Ganar, the coalition his party has formed with a host of smaller parties, including the leftist Frente Guasu. Although there are still eight other candidates beyond the two main players, the Alianza makes sense: in 2013 Alegre ran and lost but if he’d managed to cobble together the opposition he could have won. “Together we’re a majority,” he says. Nonetheless, current polls suggest the Alianza is trailing.

Not that the Alianza should be seen as anything other than an arranged marriage. In 2008 a similar coalition saw Frente Guasu’s Fernando Lugo – a charismatic former priest with a progressive agenda – sweep to power. But by 2012, his Liberal vice-president Federico Franco had turned on him in a controversial ousting on what were widely seen as trumped-up impeachment charges. Whether old wounds have really healed given the animosity between the two sides in the past remains to be seen.

Paraguay’s story can make for tragic reading. Culturally similar to its southern neighbour Argentina – Buenos Aires is home to such a large diaspora that Alegre has held campaign events there – the nation of 6.8 million was at one point the richest in South America due to its abundance of natural resources. That progress of the 19th century in the War of the Triple Alliance, when the country lost swathes of territory to Brazil and Argentina. Since then, its politics has been marked by upheaval and bloodshed, nourished by widespread patronage and graft.

There are signs, though, that Paraguay’s population is tiring. Rancour was sparked in March last year when a Colorado senator used an irregular legislative manoeuvre to proclaim himself president of the chamber and attempt to amend the constitution to allow Cartes to run for re-election (the constitution bars leaders from running more than once). Thousands took to the streets to protest. In the unrest, 25-year-old Liberal activist Rodrigo Quintana was killed when police burst into the party’s HQ in the capital Asunción. Today, the blood marks on the floor of the building have been encased in transparent plastic to permanently mark the site of the killing.

Cartes, a former football club president and owner of a soft drinks company and a clutch of newspapers, is a divisive figure. With a popularity rate of 21 per cent at the end of last year, his heir apparent for the presidency Santiago Peña lost in the primaries to Mario Abdo. The Colorado candidate now has the unenviable task of trying to unify a party licking its wounds from a brutal internal election while distancing himself from the controversial Cartes.

“We are waving a flag of an alternative within the governing party,” says Abdo, sitting in his reception room looking onto a swimming pool in one of the houses dotted around the large estate his family occupies in the capital. Yet ask about Cartes, he admits that while he is promoting “unity” he’s been highly critical of the current president. Mention Cartes’ threat against Efraín Alegre’s family and Abdo is keen to set himself apart. “Everyone owns what they do,” he says.

Abdo also comes with his own baggage. The son of the former private secretary of dictator Stroessner, he “defends” the public works carried out by the Colorado party during that time, such as the construction of the Itaipú Dam (the second-largest hydroelectric plant in the world), while saying he doesn’t agree with the human rights abuses that took place. He claims he has clearly established democratic credentials. Asked what he thinks of the work his father did for the dictator, though, and there’s a pause. “It was another time,” he says with a fixed stare.

For all the two sides’ talk of divergent paths, in many ways the two candidates are similar. Alegre talks of “listening” while Abdo organises caminatas (walks) with the people. Both tout the necessity in improving conditions for the rural poor in one of the most unequal countries when it comes to land distribution. Indeed, an average GDP growth of 5 per cent over the last decade has primarily benefited the wealthy owners of the country’s vast farms, some of them illegally inherited when land was dished out to cronies during Stroessner’s rule. Alegre talks about a justice system that has been “hijacked by political power”, while Abdo says that politicians need to have “the moral authority and the political will to not be complicit”. Both call for greater respect for institutions and an end to impunity.

What most sets Alegre apart is his choice of vice-president, Leo Rubín, a member of the Frente Guasu. Rubín is clearly the most progressive of the bunch even if, like the grand majority of politicians in Paraguay, he refuses to publicly affirm legalising gay marriage (“It merits a debate,” he says on the campaign trail. “I can’t give a yes or no.”). And yet it’s clear that he’s itching to come out with more progressive public proclamations. A necklace-wearing, yoga-practising vegetarian with a background in journalism, he runs counter to the political establishment and offers hope that a victory for Alegre could amount to real change.

Inside a colonial building in Asunción’s crumbling historic centre, Lilian Soto is sat at a table and looking sceptical of both candidates. A former minister in Lugo’s government she has kept her Kuña Pyrenda party out the current alliance because “the previous experience wasn’t good”, she says, a reference to Lugo’s impeachment. A self-declared feminist with shocks of pink hair, fighting for issues such as abortion rights, she has a tough job in a country where machismo is rife. She says this campaign cycle has seen little debate on social issues.

As elections approach, both of the main candidates are clearly treading carefully, steering clear of taboo subjects. For all its dark past, though, perhaps time is the answer for Paraguay. “Nearly 32 per cent of the population that can vote is between 18 and 29,” says lawyer and political scientist Rubén Galeano at the Autonomous University of Asunción’s downtown campus. “And they never knew Stroessner.”

A younger generation could demand change. Or it could vote for the continuation of the Colorados – already ingrained in the national psyche as the most dominant party – because they have little idea of the party’s dark past. With both sides assuring change is coming, whoever wins on 22 April has an opportunity to make sure that Paraguay – a land of Jesuit ruins, chalky-cheese chipa bread and a love of tereré, a cold drink of yerba mate and herbs – can break its cycle of chronic mismanagement. And with it, get people talking for the right reasons.

Guaraní

Paraguay is the only country in South America where the majority of the population speaks an indigenous language: Guaraní. Also spoken over the border in Argentina’s northern states of Formosa, Corrientes and Misiones, an estimated 90 per cent of Paraguayans can converse in it with some proficiency, although Spanish is still the language of administration and urban centres. According to Miguel Ángel Verón Gómez, who runs a Guaraní foundation in San Lorenzo near the capital, “Guaraní represents the identity of the Paraguayan people.” Which means it plays an important role in politics: part of the reason Santiago Peña lost the Colorado primaries was because he doesn’t speak the language; Leo Rubín has been taking lessons. Meanwhile, much of the reason Fernando Lugo connected with the rural population when he was president was due to his comfort speaking the language.